Economics Has a Bias Problem: And It’s Costing Us Billions.

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

Achieving gender equity in economics is not just a matter of fairness; it's a smart economic move. By tapping into the talent pool, we can boost innovation, improve policy outcomes, and ultimately, enhance economic growth.

Credentials versus Perception – A Stark Discrepancy

Imagine the profile that ought to command near‑automatic respect: an Oxford PPE graduate with First‑Class honors who subsequently survived the mathematical gauntlet of the LSE MSc Economics—an experience indistinguishable from the first year of a top‑tier PhD. She has internalized measure‑theoretic probability, solved dynamic‑stochastic general‑equilibrium models under uncertainty, and produced an econometrics dissertation that would intimidate half the editorial board of Econometrica. Yet when broadcasters invite her to discuss fiscal rules, they introduce her—without malice, but with chilling regularity—as “Rachel the Accountant.” This is not an isolated incident but a symptom of a systemic problem.

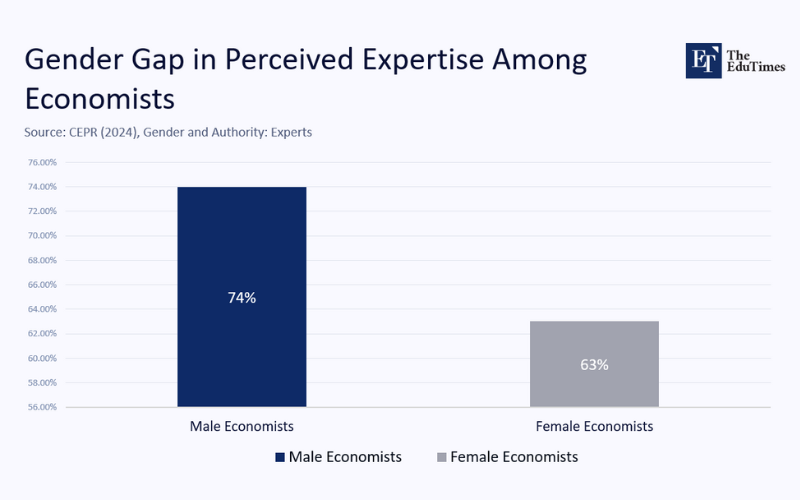

This anecdote is not an outlier. The CEPR column “Gender and Authority: Experts” reports that, when curriculum‑vitae lines are constant, women are nine to twelve percentage points less likely than otherwise identical men to be labeled “expert” by survey respondents. The survey design—single‑screen vignettes that cannot capture the full complexity of reputation—undoubtedly understates the problem. Yet, its directional finding echoes deeper literature: Heather Sarsons on referral patterns in medicine, Erin Hengel on journal referee behavior, and Lundberg & Stearns on citation gaps.

Pipeline explanations fall short. Indeed, only a third of economics PhDs in Europe and North America go to women, and the share narrows further in mathematically intense sub‑fields such as macro‑theory. However, scarcity in the pipeline does not explain differential recognition among those already through the gate. During the general equilibrium sequence at LSE, my cohort was twenty‑eight percent female; nevertheless, when invitations went out for policy round tables, the gender ratio often collapsed to single digits. Attrition, in other words, occurs after competence has been demonstrated.

Counting the Cost – A Back‑of‑Envelope Macro Simulation

Authority has economic value because it buys access to prestigious think‑tank fellowships, media bandwidth, and closed‑door advisory committees that set the tone for the fiscal and monetary debate. Empirical work by Blanes i Vidal and Möller suggests public visibility can raise an economist’s lifetime earnings by roughly one‑fifth.

Using their estimate as a proxy for marginal product, one can sketch the social cost of systematic under‑recognition. Assume the OECD employs fifteen thousand senior economists. Suppose thirty percent are women, and half suffer an authority discount of twenty percent in earnings and platform reach. If the average senior economist earns—and by revealed preference produces—about €190,000 a year, the deadweight loss from discounted female expertise already exceeds eight and a half billion euros annually. This figure is conservative: it ignores the policy errors that follow when a labor-market specialist is excluded from a minimum‑wage commission, or a banking‑regulation savant is overlooked for a crisis‑monitoring task force. The actual macro cost almost certainly lies an order of magnitude higher.

Deconstructing Misrecognition – Three Interlocking Mechanisms

Economists like tidy models and three well‑documented channels suffice to explain most of the gender gap in perceived authority. First comes role congruity bias. Decades of social psychology experiments demonstrate that people subconsciously associate “numbers plus command” with male archetypes. When a woman speaks in the clipped, equation‑laden idiom of DSGE, evaluators experience cognitive dissonance and downgrade her competence.

Second, visibility operates through feedback loops. Media producers follow a self‑referential logic: past mentions are treated as proof of expert status, so each appearance begets the next—a modest gap in 2010 snowballs by 2025 into a yawning chasm. A recent scrape of 1.8 million English‑language news articles confirms the dynamic: a single‑point deficit in initial coverage widened to 2.4 points within a decade.

Third, credentials are interpreted through a gendered lens—a phenomenon I call credential compression. This means the public reads a male economist’s MSc or PhD as evidence of macro‑policy prowess; the identical letters after a woman’s name are filed under “bean counter.” In other words, the same qualifications are perceived differently based on the holder's gender. Bohnet and Pande’s résumé experiments show identical CVs are mapped onto lower‑status roles when the candidate’s name signals femininity. It is sociology masquerading as HR.

Correctives That Match the Scale of the Problem

How, then, can the market failure be repaired? The instinctive answer—“raise awareness”—is inadequate. Instead, the profession, the media, and policy‑making bodies must re‑engineer the information architecture that feeds misrecognition. Structural changes are not just necessary, they are possible and within our reach.

Media style guides should standardize academic titles. An interviewee who has produced frontier research in identification theory deserves to be introduced as “Dr. Jane Doe, macroeconomist,” not as “Jane who crunches numbers.” The visual cue of a doctorate nudges viewers to update priors before she utters her first sentence.

Meanwhile, expert‑panel selection should rest on objective composite indices—publication impact, citation‑adjusted h‑index, and the number of central‑bank memos authored—not on the producer’s Rolodex. Algorithms can shortlist candidates using anonymized files, revealing personal identifiers only at the final stage to ensure demographic variety rather than suppress it.

Within academia, widening the pipeline remains essential but must not come at the price of diluted standards. Real‑analysis and probability boot camps, funded by elite departments and targeted at high‑potential undergraduates, can give incoming graduate cohorts—women and men from under‑represented backgrounds alike—the mathematical footing the modern discipline demands. Finally, advisory committees should publish diversity scorecards. Central banks know from the inflation‑target regime that transparency disciplines behavior; the same logic applies to expert‑panel composition.

Respect Earned Through Analytical Excellence

The environment within elite economics programs such as LSE is one of intense intellectual rigor, where exhaustion often becomes a badge of commitment. Students forge bonds over late-night derivations and cultivate a deep pride in their ability to maneuver through the technical intricacies of utility maximization and ε‑δ proofs. Yet within such demanding settings, respect is not distributed casually; it is allocated with ruthless precision to those who demonstrate genuine analytical brilliance, regardless of background or identity. When the top score on the general‑equilibrium final belonged to a woman from Peking University, everyone deferred to her in study groups. No one muttered “accountant.” The dissonance emerges outside the ivory‑tower gating mechanism, where the public’s mental shorthand still codes female faces as support staff.

Enlarging the Evidence Base – Research Imperatives

Future inquiries should push beyond binary gender splits. Intersectional analysis is overdue: does misrecognition double for a Black Frenchwoman or an Indian economist speaking with a non‑Anglophone accent? Dynamic career‑path modeling could trace PhD cohorts over forty years and convert perception gaps into lifetime earnings trajectories and downstream policy errors. And because many newsrooms now rely on AI‑powered “expert‑finder” tools, audits of those algorithms are urgent; a model trained on historically biased data will perpetuate yesterday’s injustices at machine speed.

Conclusion – Authority Must Follow Merit, or Economics Betrays Itself

Economics prides itself on allocating resources to their highest‑valued use. Talent is the rarest resource of all. To misallocate it through gendered prejudice is to violate our first principles. The Oxford‑educated, LSE‑forged economist derided as an accountant is prevented from supplying her scarce human capital where society needs it most. The bill for that error is already running into billions.

Our discipline must, therefore, direct its favorite instrument—evidence‑based policy—toward its mirror. Until the day a woman armed with stochastic calculus is instinctively introduced as the macro strategist she is, the economics profession remains trapped in a self‑inflicted market failure. And any economist worth their Lagrange multipliers knows: when markets fail, deliberate intervention becomes not merely permissible but imperative.

The original article was authored byHans Henrik Sievertsen and Sarah Smith. The English version of the article, titled "Gender and the authority of experts,” was published by CEPR on VoxEU.