[Deep Tech] ‘Cool Classrooms Are Welcome, But’

Input

Modified

Classroom Temperature Has a ‘Material Impact’ on Academic Performance Digital Device–Driven Distraction Remains a ‘Persistent Problem’ Cooling Cannot Serve as a ‘Panacea’

This article is a reconstruction tailored to the Korean market based on a contribution to the SIAI Business Review series published by the Swiss Artificial Intelligence Institute (SIAI). The series aims to present researchers’ perspectives on the latest issues in technology, economics, and policy in a manner accessible to general readers. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of SIAI or its affiliated institutions.

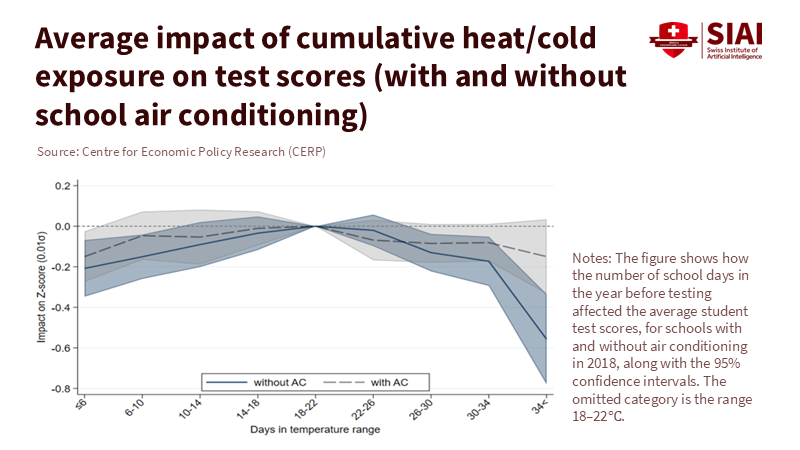

As global warming intensifies, schools are rushing to install air-conditioning systems. A Japanese study shows that on days when temperatures exceed 34 degrees Celsius, students taught in non-air-conditioned classrooms see their test scores fall by 0.56 standard deviations. When air conditioning is introduced, however, 73% of the lost performance is recovered.

Classroom Cooling and Its ‘Substantial’ Impact on Academic Outcomes

Last year, Japan equipped most public schools with air-conditioning. This marks a striking shift from 2006, when the installation rate stood at just 10%. Despite this progress, student academic performance in Japan and other countries continues to decline, indicating that factors beyond cooling are at play. Between 2018 and 2022, the average mathematics score across OECD countries fell by roughly 15 points. In South Korea, one of the top-performing nations, scores dropped sharply from 554 in 2012 to 527 in 2022.

Note: Temperature exposure range (X-axis), change in standard deviations (Y-axis), air-conditioned (dashed line), non-air-conditioned (solid line)

Policymakers have responded swiftly. New York State in the United States has codified an indoor temperature cap of 31.1 degrees Celsius, requiring schools to implement emergency measures when the threshold is exceeded. The United Kingdom, while avoiding a legally binding limit, relies on guidelines focused on risk assessment and comfort. Such measures clearly improve health outcomes and reduce discomfort, but they do not appear to automatically translate into higher test scores.

Instruction, Curriculum, and Attention Remain ‘Critical’

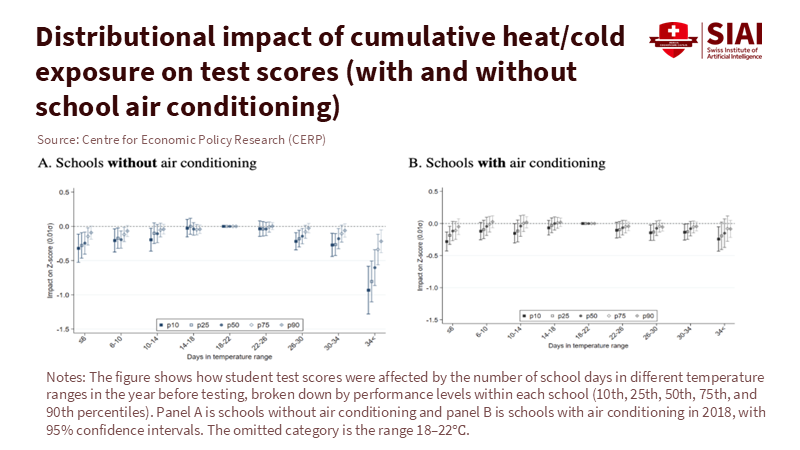

Heat does have a direct effect on learning. Research indicates that rising temperatures disproportionately harm the academic performance of low-income and minority students. Those already struggling to keep up with coursework face even greater challenges. In these circumstances, air conditioning, while imperfect, alleviates a significant share of the problem. A Japanese study that tracked individual student outcomes and compared them with local weather patterns provides evidence of this effect.

At the same time, the research also shows that investments in cooling infrastructure do not mechanically boost academic achievement. The quality of instruction, rigor of the curriculum, attendance rates, and time spent focusing on assignments remain decisive factors. OECD analyses similarly conclude that while the learning environment matters, it cannot substitute for effective teaching methods and structured study practices. In short, policies centered solely on cooling enhance comfort and safety but fail to raise academic performance on their own.

Cool, Clean Air and Its Contribution to ‘Focus’

Cooling does help reduce cognitive load—the mental effort required to process information and complete tasks—while lowering fatigue and improving attendance. High-quality HVAC systems have been shown to reduce absenteeism and suspensions, and to contribute marginally to gains in reading and mathematics scores. Cooling and ventilation mitigate thermal stress and support concentration. Yet even after accounting for these benefits, the greatest enemy of learning remains distraction.

Note: Non-air-conditioned schools (left), air-conditioned schools (right), temperature exposure range (X-axis), change in standard deviations (Y-axis) / bottom 10% performers (p10), bottom 25% (p25), median 50% (p50), top 25% (p75), top 10% (p90)

According to the 2022 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), students who reported being distracted by classmates’ mobile devices during mathematics lessons scored an average of 15 points lower. When digital device use is curtailed in a disciplined manner, scores rebound, suggesting that the core issue lies not in the devices themselves but in the distraction they generate. No matter how cool the classroom, maximizing learning outcomes ultimately requires teachers who foster concentration and structured routines.

A ‘Multifaceted Approach’ Linking Heat and Instruction

Even schools in advanced economies with state-of-the-art cooling systems struggle with breakdowns, noise, and power constraints. Standards vary widely, including in countries like the United States, which lacks a federal indoor temperature limit. Budget shortfalls, volatile electricity costs, and climate targets compound these challenges.

Addressing heat therefore calls for a multifaceted strategy. Aligning class schedules with temperature patterns—placing cognitively demanding subjects during cooler periods and lighter coursework during hotter hours—offers one practical option. New York State’s 31.1-degree benchmark, combined with such scheduling, could help preserve students’ capacity to focus on assignments.

More broadly, upgrading HVAC systems should be treated as an element of education policy. Emphasizing filter maintenance, air circulation, carbon dioxide monitoring, and regular servicing can improve comfort and academic outcomes without large-scale renovations. Restricting digital device use during key instructional periods would further enhance student focus.

Rigorous measurement is also indispensable. Schools that upgrade cooling and ventilation systems should track attendance, behavioral incidents, and academic performance, benchmarking results against comparable institutions. The ultimate objective is not cooling itself, but higher academic achievement.

Cooling can mitigate the adverse effects of heat on learning, but it is no cure-all. Student focus, curriculum design, and the overall management of the classroom environment remain enduring priorities.

For the original version of this research article, please refer to Cooler Classrooms, Cooler Heads? Why Air Conditioning Alone Won’t Fix Learning, Copyright of this article belongs to the Swiss Artificial Intelligence Institute (SIAI).