[AI Memo] AI Writing Education: From Policing to Understanding and Effective Use

Input

Modified

A shift toward reasoning- and evidence-based writing education in response to AI proliferation The need to establish transparent assessment frameworks that incorporate the process of AI use Strengthening teacher capacity and ensuring a fair learning environment as core challenges

This article is a reconstruction tailored to the Korean market based on a contribution to the SIAI Business Review series published by the Swiss Artificial Intelligence Institute (SIAI). The series aims to present researchers’ perspectives on the latest issues in technology, economics, and policy in a manner accessible to general readers. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of SIAI or its affiliated institutions.

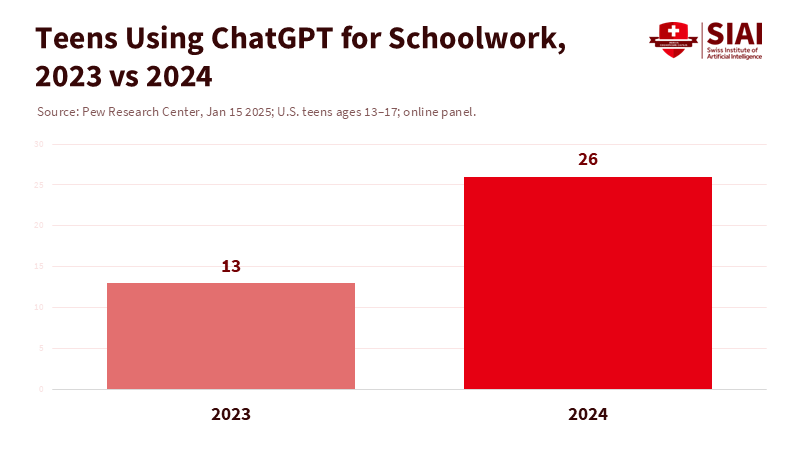

The share of U.S. teenagers using ChatGPT for academic purposes nearly doubled within a year, rising from 13% to 26%. This is not a fleeting trend but a signal of a fundamental shift in learning methods. Spreading across grade levels and backgrounds, this change indicates that classroom writing is no longer an individual endeavor, but a process increasingly shaped through collaboration between humans and artificial intelligence.

If AI writing education ignores this reality, students will repeatedly face an irrational situation in which they are penalized for using tools that are becoming essential for future learning and work, while those who conceal their use are rewarded. The issue is not whether AI should be permitted, but what competencies students must develop through its use.

Redefining Writing Education

In the past, writing was perceived as an isolated task that individuals had to complete alone. Today, however, writing has evolved into a collaborative process in which humans and artificial intelligence jointly develop ideas and refine expression. The focus of writing is shifting away from sentence-level polishing toward the ability to reveal the flow of thought and substantiate arguments.

Note: Year (X-axis), usage rate (Y-axis)

AI writing education must redefine the meaning of literacy. At its core are the abilities to develop questions into evidence-based claims, analyze and verify sources, collaborate with AI to construct drafts, and clearly articulate one’s own reasoning. To achieve this, more instructional time should be devoted to teaching argument design rather than grammar correction. Structuring claims and evidence, systematic note-taking, and brief oral presentations are concrete methods. Students must learn the principle that while AI can be an efficient tool, judgment and responsibility remain human obligations.

These changes are already being detected in educational settings worldwide. Recent policy directions have shifted away from banning AI toward establishing principles for human-centered use. Yet many countries still lack clear guidelines, and schools have been slow to adopt validated educational tools. The direction, however, is clear: use AI, but manage the thinking process transparently.

A Shift Toward Assessment-Centered Reform

If assessments favor students who conceal AI use, students will do exactly that. If, instead, assessments emphasize transparency of reasoning and evidence, students will disclose their process and clearly present their sources. Accordingly, AI writing education must redesign assignments around verifiable evidence and clarity of expression.

Assignments should move away from formulaic essays toward engagement with real-world issues. Examples include analyzing local budget expenditures, comparing and evaluating policy reports, or re-examining existing arguments using newly released statistical data. Tasks that require students to present their proposals in short presentations of around three minutes, based on their own research, are also effective.

All assignments should require the submission of a process report. This report must include the prompts used, the scope of AI involvement, the sources consulted and their verification procedures, and a methodology note of approximately 100 words. While the completed text evaluates outcomes, the report assesses the student’s thinking process. Evaluating both together ensures transparency of learning and academic integrity.

The methodology note should be concise but specific. For example: “I used an AI assistant to draft an outline, and completed paragraphs two through four after receiving advice on structure and tone. Statistical data were cross-checked against original datasets from the Pew Research Center and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, with errors corrected after two rounds of verification.” The goal is to enable teachers to move beyond surveillance and instead assess the quality of reasoning and evidence.

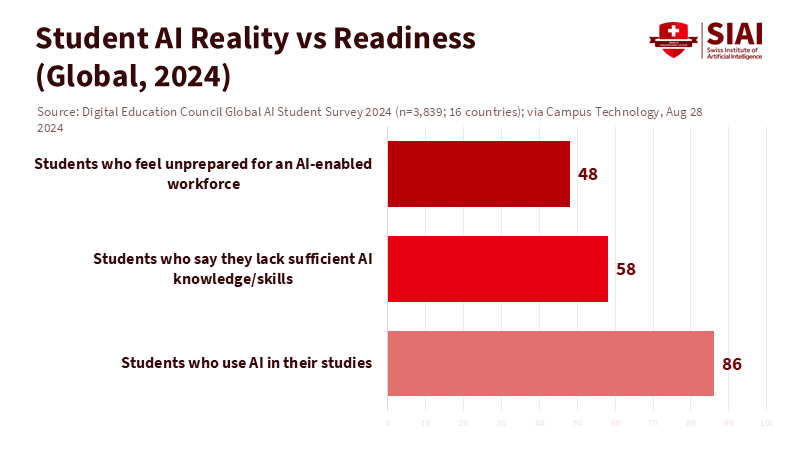

This approach also aligns with student demands. In a 2024 survey of 3,839 university students across 16 countries, 86% reported already using AI for academic work, yet 58% felt they lacked sufficient understanding of AI, and 48% believed they were unprepared for an AI-centered work environment. This gap is precisely what new writing education must address. A system that teaches and evaluates verification, disclosure, and context-appropriate expression is required.

Note: Response rate (X-axis), response categories (Y-axis) / Percentage of students using AI for learning, percentage feeling they lack AI-related knowledge and skills, percentage feeling unprepared for AI-era employment environments (from top)

The Limits of Detection Technologies

More schools are relying on detection tools to curb AI misuse, but this approach fails to address the fundamental issue. Even developers acknowledge accuracy limitations. OpenAI discontinued its text classifier due to low reliability, and major universities and educational institutions advise against using detection results as grounds for disciplinary action. Turnitin, a widely used plagiarism detection software, also withholds AI detection results when confidence levels fall below 20% in order to reduce false positives.

The limitations of detection tools are evident. There are cases in which carefully polished student writing is mistakenly identified as AI-generated. Detection may serve as a reference, but it must never stand alone as a basis for judgment. Education policy must reflect this reality.

Moreover, directly using detection results for disciplinary measures poses legal and ethical risks. Cases in which students were sanctioned based on ambiguous rules and low-reliability technologies have already escalated into legal disputes. This erodes trust among teachers, students, and administrators and generates unnecessary conflict. Sanctions must therefore never rely solely on detection results, and evidence must always include documentation of the writing process and source verification.

Strengthening Teacher Capacity and Educational Equity

Teachers must acquire new instructional skills, including prompt design, source verification, and process-based assessment. Despite ongoing teacher shortages, such retraining is no longer optional. Educational authorities’ medium- and long-term plans increasingly identify not only teacher recruitment but also the capacity to perform these new roles as a core task.

Teachers are now expected to use AI as a supplementary educational tool. Their role includes co-designing writing processes and providing feedback centered on logic and evidence. Examples include demonstrating verification procedures in real time during class or conducting brief oral presentations in which students explain why they chose specific claims and sources. These instructional methods prioritize reasoning over mere replication and reduce AI misuse.

Ensuring a fair learning environment is equally critical. Paid AI services must not become instruments that widen educational gaps. Schools should institutionally support access to reliable, shared AI tools. Clear disclosure standards are also needed to ensure that non-native speakers are not penalized simply for using grammar correction functions.

The core of AI utilization education lies in teaching appropriate use. AI may be employed to expand ideas or verify data, while organizing thoughts and refining expression should remain student-driven. This distinction is not about replacing writing training, but about concentrating on essential competencies.

The Direction of Education in an Era of Change

The purpose of AI writing education is not control, but capacity building. Proper use of artificial intelligence can clarify thinking processes, enhance expressive quality, and improve fairness in assessment. Students must learn how to formulate claims, verify evidence, and rationally leverage available assistance. Even without reliance on detection technologies, academic integrity can be ensured by jointly evaluating process and outcome. Schools must establish accredited tools and clear guidelines to narrow gaps between teachers and students, while strengthening data protection frameworks.

If education remains anchored to traditional writing standards that exclude AI, it will fail to keep pace with reality. Future writing education must place evidence and verification at its core and advance through transparent processes that build trust.

For reference, the original version of this research article is AI Writing Education: Stop Policing, Start Teaching. The copyright of this article belongs to the Swiss Artificial Intelligence Institute (SIAI).