[Deep Tech] Lessons From Smartphone Regulation, a New Benchmark for School AI Policy

Input

Modified

Smartphone bans as a blueprint for school AI policy Age-tiered access and transparent procurement as the foundation for AI use standards Evidence-based evaluation and teacher-led governance to strengthen learning focus and fairness

This article is a reconstruction tailored to the Korean market based on a contribution to the SIAI Business Review series published by the Swiss Artificial Intelligence Institute (SIAI). The series aims to present researchers’ perspectives on the latest issues in technology, economics, and policy in a manner accessible to general readers. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of SIAI or its affiliated institutions.

Forty percent of education systems worldwide already restrict smartphone use in schools. As of late 2024, 79 countries had implemented laws and policies that ban or limit smartphone use on campus. This shift illustrates how societies absorb and regulate new technologies. The pattern is consistent: adoption comes first, impacts and side effects are assessed, and rules are then established to protect students. The experience forged around smartphones now needs to be applied to large language models (LLMs).

Both technologies are deeply embedded in everyday life, and both are designed to capture and hold attention. The result has been diminished student concentration and weaker learning immersion. The question now turns to how quickly and clearly AI policy can be built, drawing on the smartphone playbook.

Lessons Left by Smartphones

Restrictions on smartphone use are increasingly viewed as a tangible outcome of education policy responding to technological change. UNESCO has documented how scattered guidance across countries evolved, over a short period, into national-level bans or restrictions. The number of countries implementing such policies expanded from 60 in 2023 to 79 by late 2024.

The policy shift moved fast. The United Kingdom, in February 2024, issued national guidance enabling headteachers to restrict mobile phone use during class. The Netherlands banned use in classrooms except for learning or accessibility purposes and recorded high compliance soon after implementation. Finland, starting in 2025, will restrict device use during lessons and grant teachers the authority to confiscate devices that disrupt learning.

These measures reshaped the learning environment. The prevailing rule became keeping devices unrelated to learning or health outside the classroom, which translated into higher student focus and the restoration of teachers’ instructional authority. According to PISA 2022, roughly two-thirds of OECD students reported feeling distracted by smartphones during math class, and their average scores were lower than those of students who did not report such distraction. In Australia, one year after nationwide restrictions, 87% of 1,000 school administrators in New South Wales said in-class distraction had declined, and 81% said learning outcomes had improved.

Estonia, however, chose “controlled device use” and AI literacy education instead of a ban. Rather than limiting devices outright, it adopted an approach that places teachers at the center and integrates technology into instruction. UNESCO assessed such efforts positively while also noting that research and evidence remain insufficient relative to the speed of technological change. The core issue ultimately lies in moving beyond a ban-permit binary and establishing clear boundaries that enable safe, education-aligned use of technology.

Note: Year (X-axis), restriction adoption status (Y-axis) / Number of education systems restricting smartphone use (light red), share of all education systems adopting restrictions (dark red)

Direction for Designing School AI Policy

Bringing AI into school education will stand as a central task for future education policy. The experience with smartphone policy shows that effective regulation needs to remain simple while staying grounded in operational reality. Exceptions can be recognized for educational necessity such as learning objectives, health, and accessibility, while data protection needs to be strengthened.

The risks introduced by AI extend beyond attention erosion. Student data may be collected indiscriminately, and excessive reliance on AI may take root. The risk of misinformation affecting evaluation or grades is also substantial. In 2024, 70% of U.S. teenagers used generative AI, and 40% used it for learning. In the same year, a Pew Research Center survey found that 25% of U.S. K–12 teachers said AI harms education, while 33% assessed positive and negative effects as roughly balanced. These findings show a widening gap between rapid AI diffusion and the still-thin standards for response and use in schools.

Policy design should be refined around age-tiered access rules. Students under 13 should be limited to dedicated tools managed by schools, with chat content set to avoid being stored. Ages 13–15 should be allowed access only via school accounts, with usage logs and content filtering made mandatory. Students 16 and older should be permitted to use AI only under teacher supervision, with clear disclosure of purpose and sources.

Governance standards are also required at the adoption stage. During contracting, schools should configure settings so that minors’ account data does not automatically persist, and age verification should be conducted in a way that does not collect personal information. Teachers or administrators should be able to disable AI chat functions or extensions when needed, and vendors should disclose reports detailing data-handling practices and safety-validation results.

Evidence and Evaluation for AI Policy

Unlike smartphones, evidence on AI’s learning impact remains limited. With smartphones, the association between distraction and lower academic achievement is clear, while definitive proof that bans directly raise grades remains absent. Even in Australia, positive change was reported, yet much of it rested on surveys of school administrators.

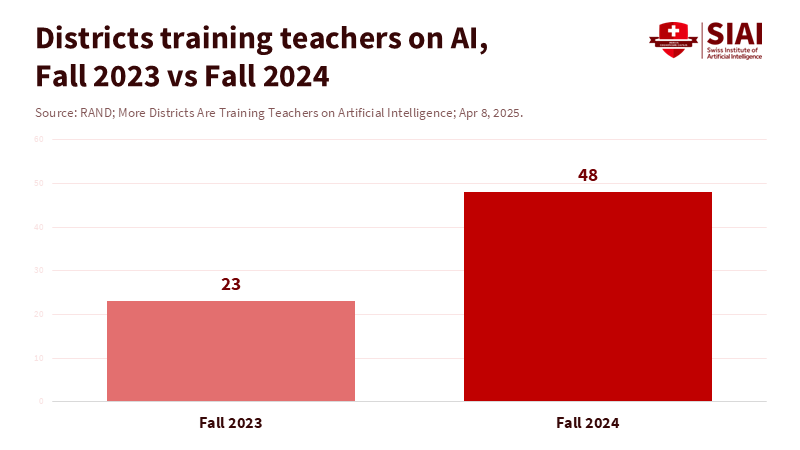

AI carries greater uncertainty. As of fall 2024, 48% of U.S. school districts had implemented AI teacher training, doubling within a year, and 72% of teenagers were using AI conversational services. More than half of students said they use them regularly. This points to risks that extend beyond learning tools toward emotional dependency or distorted relationships. Policy needs to draw a clear line at this point.

Note: Time point (X-axis), teacher-training share (Y-axis)

The research base is still in an early phase. PISA 2022 surveyed 690,000 15-year-old students across 81 countries, and the 59–65% distraction share reflects the OECD average. Common Sense and RAND materials are sample-based U.S. surveys that remain limited to trend detection. The cases of the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Finland also remain in early implementation stages.

Accordingly, AI policy needs to place its center of gravity on evaluation. Every school district should include a clear evaluation plan when adopting AI and should continuously track outcomes such as teacher workload reduction, plagiarism reduction, and learning gains for low-income and disabled students. Results should be disclosed on a regular basis, and trust in the field needs to begin with transparent evaluation.

The Path Schools Need to Take

The experience of smartphone regulation showed what is required when technology enters schools. Schools have already learned that introducing technology without clear rules can destabilize instructional quality. That lesson applies to AI as well.

Generative AI is spreading rapidly across all subjects and learning processes. Ambiguous standards can produce divergent interpretations across schools and widen access gaps among students. Simple and consistent policy can raise learning focus, protect fairness in assessment, and help students use technology appropriately. What is required now is execution. Age-tiered access standards, transparent management of usage logs, clear procurement procedures, and systematic evaluation need to form the core of policy. Once these principles take root, schools can sustain learning quality and fairness even amid accelerating technological diffusion.

Please refer to the original research article, From Smartphone Bans to AI Policy in Schools: A Playbook for Safer, Smarter Classrooms. The copyright for this article belongs to the Swiss Artificial Intelligence Institute (SIAI).