[AI Memo] AI Reshaping Infant Development Environments, Urgent Need for Interaction-Centered Standards

Input

Modified

The spread of AI devices and connected toys into infant development environments The core challenge lies in preventing data misuse while establishing design standards that promote interaction Institutionalization across policy, education, and households, alongside equity safeguards, is essential

This article is a reconstruction tailored to the Korean market based on a contribution to the SIAI Business Review series published by the Swiss Artificial Intelligence Institute (SIAI). The series aims to present researchers’ perspectives on the latest issues in technology, economics, and policy in a manner accessible to general readers. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of SIAI or its affiliated institutions.

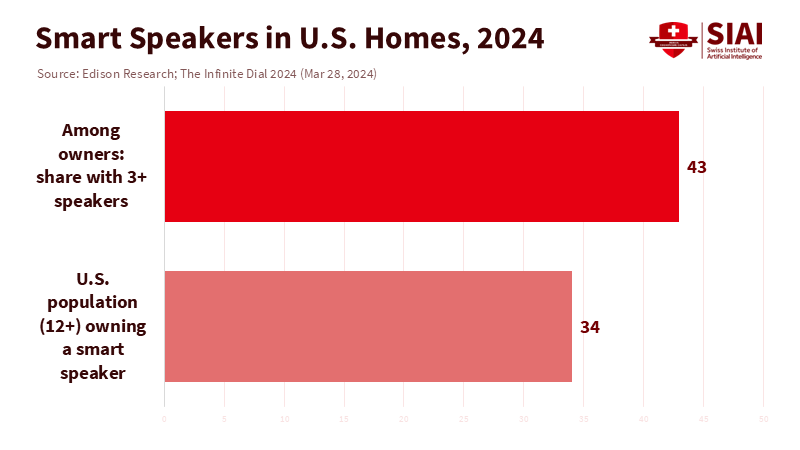

Artificial intelligence is rapidly permeating the environments in which infants grow and develop. In the United States, one-third of the population aged 12 and older owns a smart speaker, and many households install such devices throughout the home, exposing infants even as they sleep, babble, and play. The market for connected toys is also expanding rapidly and is projected to grow into a tens-of-billions-of-dollars industry within the next decade. AI has already embedded itself in the lived reality of infant development.

The critical issue is direction. Society must decide whether to permit devices that collect data while weakening human interaction, or to establish regulations and standards that strengthen communication between parents and children. During the first 1,000 days of life, the highest priority must be immediate conversation and physical interaction between parent and child.

Evaluation Standards for AI Toys

The key issue is not simply whether a device uses artificial intelligence. What matters is whether it replaces the role of parents or facilitates interaction. Language and cognitive development in early childhood depend on the rapid back-and-forth exchanges known as “serve-and-return” interactions. Research consistently shows that the frequency of conversational exchanges between parents and children has a greater impact on language development and later achievement than the sheer number of words a child hears. This has been demonstrated across multiple methodologies, including audio-recording observations and neuroimaging studies. Accordingly, policy attention should focus not on AI that talks directly to babies, but on tools that increase interaction between parents and children.

This principle also explains why video viewing continues to have negative effects on infant development. Pediatric guidelines recommend that children under 18 months avoid screen viewing, except for video calls, and that even older infants be limited to high-quality content viewed together with adults. Neurophysiological research supports the same conclusion. Infants learn best through voices that respond to their sounds, faces that move in synchrony with expressions, and hands that jointly manipulate objects. No matter how sophisticated, video cannot provide this kind of reciprocal responsiveness. Devices that cannot demonstrate the benefits of responsive human interaction should not be incorporated into infants’ daily lives.

Note: Smart speaker ownership rate among the U.S. population aged 12 and older (34%); share of owners with three or more devices (43%)

Necessary Safeguards

The debate surrounding AI toys is not about blanket permission or prohibition. The core task is to establish standards that distinguish desirable designs from problematic ones. Only then can parents, educators, manufacturers, and policymakers operate within an environment of trust.

First and foremost, data protection is critical. Some smart toys have transmitted children’s behavioral data to corporate servers without encryption. For infant products, this constitutes a serious risk. The United States has strengthened regulations on children’s personal data, restricting commercial use without parental consent, while Europe has banned targeted advertising aimed at minors. Although not all issues have been resolved, minimum standards are now in place. Devices that collect data without authorization, create opaque user profiles, or are designed to maximize usage time should no longer be acceptable.

Verification of effectiveness is also essential. Claims of improved language development must be supported by independent research. Outcomes should be assessed using objective indicators such as the frequency of parent–child conversations, standardized developmental assessments, and measures of sleep or stress. Studies must be conducted at sufficient scale and with rigorous methodologies.

Toy design should prioritize shared play. AI toys for infants should be structured to respond to a child’s sounds in ways that prompt parental engagement, and they should automatically shut down when a caregiver is not present. Data processing should, in principle, occur on-device, with clear disclosure of collection purposes and retention periods. Evaluation criteria should emphasize not usage time, but how often and how effectively parents and children communicate.

Equity considerations must also be addressed. Economically advantaged households can more easily access educational toys, speech therapy, and parental education, while less affluent families face persistent disadvantages. If AI toys remain premium products, or if free offerings rely on data extraction as compensation, disparities will widen further. Public spaces such as libraries and health centers should provide access to validated products alongside parental education programs.

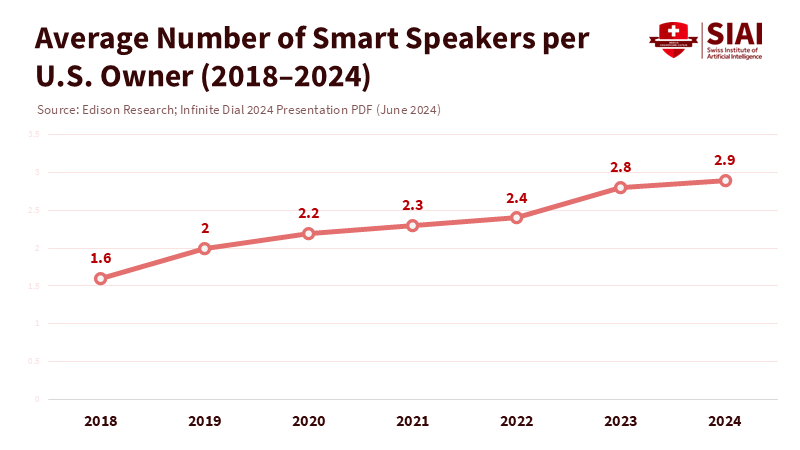

Note: Year (X-axis), average number of devices per household (Y-axis)

What We Should Build

Future AI toys should serve not as substitutes for parent–child interaction, but as complements that reinforce it. The essential goal is to encourage adults and children to converse more frequently and engage in shared play.

For example, a screen-free doll could be equipped with sensors and voice recognition. When an infant grasps a block and makes a sound, the device could signal a nearby caregiver. Once the caregiver responds, the device would cease operation, avoiding disruption of the conversational flow. Parents could later review interaction patterns and research-based guidance through an app.

Applications are also possible in early childhood education settings. During reading sessions, a small device could recognize specific words and suggest questions to teachers. Rather than reading the book itself, the device would help teachers engage children in deeper dialogue. Some studies have shown that such tools increase children’s questions and participation.

Policy and Practice

Educational settings must move beyond the mere introduction of devices to establish clear usage standards. Childcare programs should integrate language-centered interaction into teacher training, ensuring that AI tools function as supplements to, rather than drivers of, communication. Over time, the goal should be to strengthen teacher involvement rather than allow devices to dominate interactions.

Parents also require clear guidance. Products without proven effectiveness cannot be trusted, and devices that require separate registrations or excessive data permissions to function are difficult to regard as child-centered designs. For infants, cutting-edge features are irrelevant. What matters is fostering natural growth in language and emotional connection in everyday life. Beneficial AI should remain in the background, with the parent’s voice at the center.

Policy must institutionalize these principles. The United States has reinforced child privacy regulations to limit data commercialization without parental consent. Regulatory frameworks in Europe and the United Kingdom likewise emphasize the best interests of the child and data minimization. Enforcement authorities should prioritize connected toys and infant monitoring devices for scrutiny, extending beyond formal inspections to include substantive technical reviews and data analyses. When corporate claims and data are rigorously examined, products can be guided toward designs centered on shared play and safety.ㅁ

Future Challenges

Voice-based devices, like radios and smartphones before them, are now embedded in everyday life. The crucial question is how society chooses to use this technology and what roles it assigns. Privacy regulations must be strengthened to block excessive data collection, and any claims regarding developmental benefits must be backed by evidence. Devices should be developed that do not disrupt parent–child interaction but actively promote it, accompanied by policies that ensure equity by prioritizing support for families most in need.

The objective of policy choices is clear: to develop and disseminate technologies that enrich conversation, contact, and trust during infancy.

For the original version of this research article, please refer to Not Guinea Pigs, Not Glass Domes: How to Design AI Toys That Help Babies Learn. Copyright of this article belongs to the Swiss Artificial Intelligence Institute (SIAI).