[Deep Tech] Europe’s STEM Major Divide Shaped by Wage and Employment Structures

Input

Modified

STEM major choices driven by wage levels and employment risk rather than gender Finland favors interest-based choices, while Spain gravitates toward high-return majors Subsidies, income-linked repayment schemes, and disclosure of major-specific data proposed as solutions

This article is a reconstruction tailored to the Korean market based on a contribution to the SIAI Business Review series published by the Swiss Artificial Intelligence Institute (SIAI). The series aims to present researchers’ perspectives on the latest issues in technology, economics, and policy in a manner accessible to general readers. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of SIAI or its affiliated institutions.

Wage disparities by field of study across Europe directly reflect national economic structures and labor market conditions. As of October 2024, the median monthly starting salary for newly hired engineers in Finland stood at approximately $4,300, about 12% higher than the roughly $3,850 earned by humanities graduates. By contrast, in Spain, newly graduated industrial engineering majors earned an annual salary of about $42,000, 57% above the national median income for higher-education graduates and nearly double the most common salary level nationwide.

Such return differentials shape students’ choices of academic majors. In environments where wage gaps are narrow and welfare systems absorb early-career risks, students place less weight on economic considerations. Where rewards are large and unemployment risk is high, enrollment concentrates in high-return fields. This pattern is not driven by gender, but by differences in the structural incentives that guide major selection.

Structural Drivers of Major Choice

Current debates in advanced economies often attribute gender-based segregation across majors to cultural norms, confidence gaps, or school environments. Viewed through a labor economics lens, however, the same data allow for a different interpretation.

Finland’s wage system, anchored in strong unions, progressive taxation, and income-linked welfare, keeps inter-major wage gaps narrow. In such an environment, the economic incentive to pursue demanding majors in mathematics or engineering remains limited. Spain, by contrast, combines a weaker social safety net with one of the highest youth unemployment rates in Europe, producing a clear preference for majors associated with stable employment and high pay. When risk is socially pooled and rewards are similar, interest guides choice; when risk is individualized and rewards diverge sharply, economic calculation takes precedence.

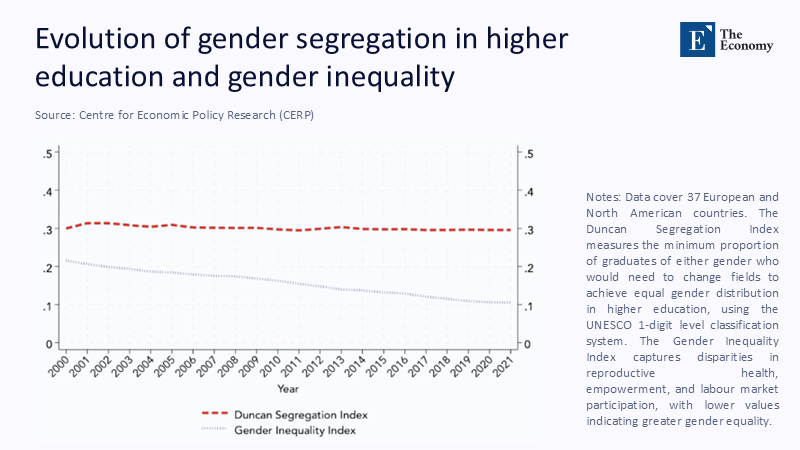

Note: Year (X-axis), Index value (Y-axis) / Gender segregation index (red line), Gender inequality index (dotted line)

Wage Gaps by Major

An analysis of 4,100 observations from the 2024 labor market survey conducted by the Finnish Association of Graduate Engineers (TEK), divided into deciles, shows that the gap between the top and bottom deciles for engineering graduates was approximately $8,600, with a risk-adjusted return index of 0.24. For humanities graduates, the corresponding figures were about $7,600 and 0.21, indicating minimal differences.

Applying the same methodology to Spain’s 2025 major-specific wage data yields a gap of roughly $24,600 for engineering majors and about $10,300 for humanities graduates. The risk-adjusted return indices stood at 1.08 and 0.46, respectively, indicating that inter-major return differentials were far wider in Spain than in Finland. In other words, choosing humanities in Finland entails little penalty, whereas in Spain the income premium associated with engineering remains substantial.

Teenagers’ Major Choices

Some argue that teenagers fail to recognize structural differences in labor markets. Survey evidence suggests otherwise. In March 2025, a Conference Board survey of 11,000 final-year high school students across nine EU countries found that adjusting expected wages by 20% prompted 82% of respondents to say they would change their intended major.

Supplementary surveys conducted in urban high schools in Tampere, Finland, and Valencia, Spain, produced similar results. When expected income was incorporated into the analysis, gender had no statistically significant effect on STEM preferences, while wage outlook emerged as the decisive factor.

Note: Propensity of women to enter STEM (X-axis), Gender inequality index (Y-axis) / Linear regression line (dotted)

Notably, when the perceived probability of post-graduation unemployment increased, Finnish female students’ likelihood of choosing information and communications technology majors declined by 11%, while in Spain it rose by 8%. Researchers attribute this divergence to the interaction between “major-specific wage gaps” and “welfare levels.” In Finland, limited wage differentials mean that riskier majors offer little additional reward, and stable welfare systems reduce incentives to assume risk. In Spain, wide wage gaps and weaker social safety nets encourage students to offset higher employment risk by pursuing majors with larger income premiums.

Post-Pandemic Labor Shortages in Europe

Europe’s post-pandemic labor shortages have heightened the need to reassess the structural factors influencing major choice. Between 2014 and 2024, low-skilled jobs in Europe declined by 2.3 million, while positions requiring a university degree increased by more than 20 million. Hiring times in STEM fields were more than three times longer than in law or journalism.

According to Randstad Research, Spain will require an additional 75,000 engineers by 2030 to meet its recovery fund targets, while Finland faces a shortage of data scientists amid rapid population aging. Experts warn that policies framing gender gaps solely as “confidence issues,” while ignoring the risk–reward signals embedded in wage structures, risk devolving into fiscally costly but ineffective public relations initiatives.

Policy Tasks for Risk Mitigation

Finland could consider introducing a tax-exempt subsidy of about $6,600 for low-income STEM freshmen, benchmarked to union-recommended wages. Such a measure would raise net entry-level pay by roughly 15%, expanding choice for risk-averse students. Analysts suggest the funding could be secured through a 0.1 percentage point adjustment to corporate R&D tax credit rates.

Spain is weighing an expansion of Income Share Agreements (ISA) currently operated by some universities. Under the proposal, repayment would begin only when annual income exceeds approximately $18,700, with payments capped at 13.2% of disposable income. An analysis of Eurostat data indicates that such schemes halve income volatility among female physics graduates and reduce lifetime gender income gaps by 8 percentage points.

Counterarguments and Responses

Some contend that Nordic women favor people-oriented professions. However, the 2025 Global Gender Gap Report shows that Iceland, Norway, and Finland rank at the top in gender equality while female STEM enrollment remains below 28%. If gender equality were the primary determinant, outcomes would be reversed.

Others argue that social stereotypes portraying women as unsuited for STEM undermine girls’ performance and confidence. Yet a 2024 analysis of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) data found that once expected post-graduation income was accounted for, gender differences in self-efficacy disappeared. This suggests that lower confidence among female students reflects rational responses to unfavorable wage prospects rather than purely psychological factors.

OECD workforce projections also counter concerns that subsidies would overcrowd certain majors. European engineering programs could absorb an additional 17% increase in students before returning to pre-pandemic faculty-to-student ratios, indicating that policies targeting risk structures remain feasible.

Completing Reform Through Measurement

To enhance policy effectiveness, authorities should publish, on a quarterly basis, four bundled indicators: median income three and five years after graduation by major, income volatility, student loan delinquency rates, and hiring lead times for core STEM occupations. Finland already collects some of these metrics, and Spain’s statistical office plans to release detailed data from the second quarter of 2025.

Integrating these indicators into high school career counseling programs would allow students to adjust wage and risk parameters directly when planning their educational paths. In Andalusia, Spain, the introduction of an integrated dashboard reduced gender bias in physics course selection by one-third within a single semester.

Once indicators are public, fiscal authorities must also be accountable for outcomes. If subsidies or ISAs successfully mitigate risk dispersion, the data will confirm it; if not, budgets can be reallocated elsewhere. Transparent metrics transform budget execution into a verifiable experiment and, over time, provide a public data foundation for research and policy design.

From Insight to Incentives

Europe’s STEM gender divide stems from differences in economic incentives. Where wage gaps are narrow, as in Finland, interest guides choice; where gaps are wide, as in Spain, returns dominate. Practical measures—such as subsidies lowering entry barriers, income-linked tuition schemes, and disclosure of major-specific income and employment data—remain essential. When risk and reward are balanced, students choose majors aligned with their skills and interests regardless of gender. Adjusting incentives today sets the conditions for the next generation to pursue a wider range of pathways.

For the original version of this research article, please refer to Choice, Risk, and the STEM Gender Divide—Why Pay Matters More Than Policy. Copyright of this article belongs to the Swiss Artificial Intelligence Institute (SIAI).